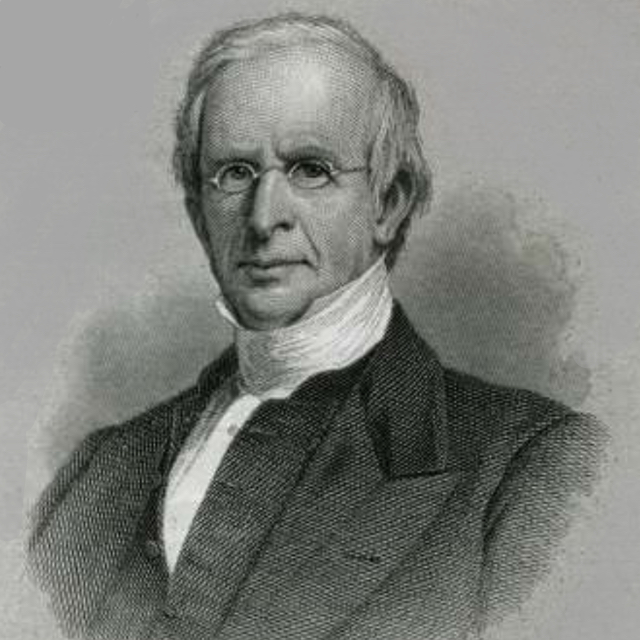

It would be profitable in some ways for every prospective missionary to be shut in a room with Rufus Anderson for a day and to be told to listen, not to speak. That would be impossible because Anderson died almost 150 years ago. He lived from 1796-1880. Yet it would be useful to be subject to his thinking through his writings. Anderson’s thinking on missions was very radical. He stripped the work of cross-cultural mission down to its leanest and most Pauline form.

Anderson had a boyhood call to foreign missions which was developed in college (he graduated in 1818) and in Andover Seminary (he graduated 1822). He offered himself on graduation for overseas service as a missionary to India. However, having worked at the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) as an assistant while studying at Andover, he was asked to remain at mission headquarters. Later he was appointed the ABCFM assistant, then senior, secretary. In 1832 he was given total responsibility for ABCFM overseas work. He became the principle policymaker and administrator. He travelled widely in Latin America (1819,1823-1824), the Mediterranean and Near East (1828-1829, 1843-1844), India, Ceylon, Syria, and Turkey (1854-1855), and Hawaii (1863). He and his wife were renowned for hospitality to missionaries.

Anderson believed mission work should only involve:

• converting lost men and women to faith in Jesus Christ,

• organising them into churches,

• giving these churches competent indigenous pastoral leadership,

• thus always guiding them to independence and to self-propagation.

Anything beyond this, he felt, was secondary to missionary work. Put another way, Anderson believed that mission work should aim at nothing more or less than the establishment of self-supporting, self-governing, and self-propagating churches. Conversion and the establishment of truly indigenous and missionary churches are best accomplished by proclamation of the gospel through preaching.

There were some basic foundations underlying his thinking:

• The language in which the missionary works. Anderson urged that educational work for the preparation of native pastors and their wives be conducted only in the vernacular or local language.

• Investment in schools, presses, and other institutions should be minimal. For Anderson, mission work was about preaching the Gospel.

• Missionaries should move out of central stations into the villages and should tour the countryside. The idea that missionaries should live together on the field in “mission headquarters” was foreign to Anderson.

• The missionary was not to be a pastor or ‘ruler’ but an evangelist, moving on to the next place as soon as possible; their business was with unbelievers, not believers. Native ministers were to be the spiritual leaders. Anderson subscribed to the idea that a missionary should be working himself or herself out of a job. Having preached the gospel and planted a church, they should be looking to hand it over to indigenous leaders as soon as they could when the local leaders were trained sufficiently to take it over. So native pastors should be ordained speedily. Congregations should form their own ecclesiastical organisation, with the missionary serving only as a helper for a limited time.

• Anderson had a strong view on the separation of the gospel from the task of bringing 'civilisation' to the country in which the missionary worked. To Anderson, civilisation was not a legitimate aim of mission but rather that would come through the life-changing impact of the gospel. This went against the nature of mission in his time which tended to start with civilisation of “the natives”. Thus exclusively educational work if separated from the gospel was not acceptable to him. Indeed at one point he even closed down a seminary in Sri Lanka because he felt that it was not fruitful enough in winning folk to Jesus. He wrote that Bible translation, literature, schools, press, and all other activities should be directed to building a mature local church that evangelised and sent out missionaries.

• He prohibited any mission from becoming engaged with a government or engaging in any kind of business.

• He advocated cooperation with other societies to avoid the waste of people and money.

In summary, Anderson strongly promoted the "three-self" concept of missionary work, the need for creating churches that were self-supporting, self-governing, and self-propagating. His thinking relates closely to three other missionary thinkers that I have written about recently: Henry Venn; John Nevius; and Roland Allen.

I would highly recommend any prospective missionary or mission strategist, or indeed church leader involved in missions, going back to look at the other three men and Anderson.

Anderson’s thinking may have been a little too radical or perhaps it was specifically related to the time in which he lived. For example, business as mission is required even to exist in mission work in some nations today. But the principles of these four mission thinkers need to be re-visited frequently.

Sources: Wikipedia; Boston University School Of Theology.