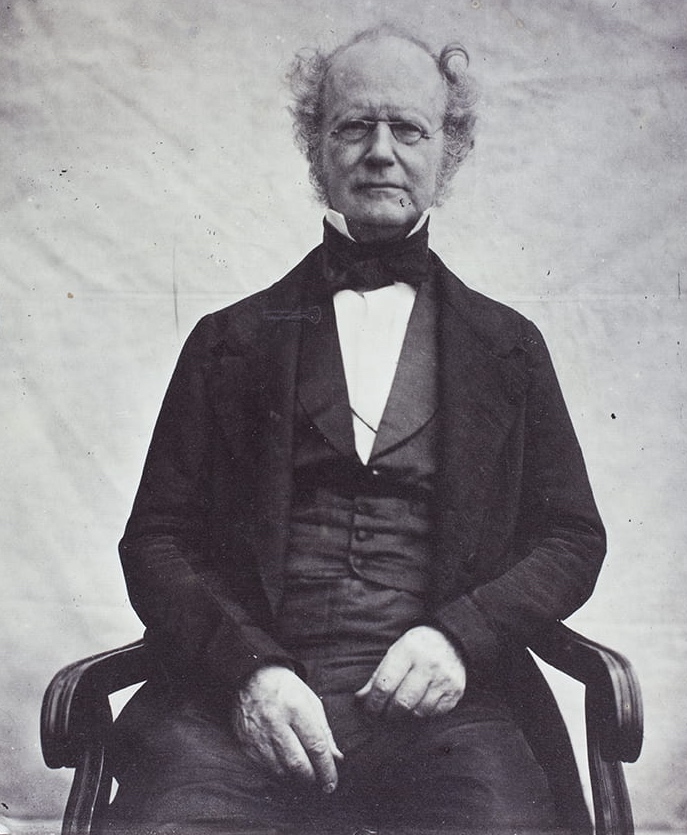

Walter Henry Medhurst (1796-1857), was an English Congregationalist missionary to China. He was one of the early translators of the Bible into the Chinese language. It is hard to do him justice and a much fuller account of his life can be found in the Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Christianity (see link below).

His death came fifty years after Robert Morrison had embarked for China, thus ending the cycle of the first fifty years of Protestant missionary work in China. “William Muirhead, preaching at his funeral in London, said he was the last of China’s first missionaries. An epoch had ended. Shanghai would never be the same again.” “The last of China’s first missionaries” - the last of the generation of Robert Morrison. Medhurst was a historic figure.

I will look at him in geographic terms. Born in England, “he responded to an advertisement for a printer to join the London Missionary Society (LMS) and was accepted for a position in Malacca (now Malaysia). He sailed to Madras, India, in 1816. “There he met Betty Braune, who at the age of twenty-one was both an orphan and a widow with a young son, George, who was six” (no comment on that last sentence!). Before he left for Malacca he had fallen in love with Betty and proposed to her. They were married just before their ship departed. Betty’s son George, whom Medhurst had adopted, accompanied them. Over the years they had a number of their own children, at least five of whom died while young.

They arrived in Malacca in 1817, where the LMS had set up the headquarters for all their missionary ventures outside of India. Walter kept busy, “including preaching, schools, printing, and tract distribution” along with learning Chinese - the rudiments of Cantonese, Hokkien, and Mandarin, while he distributed tracts among the Chinese living on river junks and in surrounding villages. Medhurst took charge of the three Chinese schools run by the mission and continued to superintend the English, Chinese, and Malay printing operations.

Then came Penang. Increasingly frustrated with the situation in Malacca, he decided to start another LMS work in Penang. “He often went to a Daoist temple to discuss religion with the monks. He had a way of communicating his ideas without raising the ire of his listeners. He distributed books and pamphlets, which the recipients retained and read.”

Then came Batavia (modern Jakarta) where he laboured for 21 years. Walter preached weekly in Chinese at four stations around Batavia, both in Hokkien and in Mandarin. He also held services in English and Malay at the English chapel on the mission property every Sunday. The printing establishment of the mission centre produced a Chinese magazine (1,000 copies a month) as well as books and pamphlets. He also ran a small dispensary from his home. “The big difference between Medhurst and his fellow missionaries in the region was his ability to communicate with the people. He was one of only a handful of early Protestant missionaries who acquired fluency in two spoken Chinese dialects and he was able to draw bystanders into discussion, explaining a section of the Bible in their own terms.’

The LMS decided in 1843 to make Shanghai their headquarters in China, with the press and a hospital at the core of the mission. Medhurst worked in Shanghai for twelve years. He traversed the provinces of Zhejiang, Jiangxi, Anhui, and Jiangsu with a Chinese guide.

Apart from his considerable work of translating the Bible into Chinese, perhaps his most significant legacy was the investment into the lives of others, particularly Hudson Taylor. His major book, “China: Its State and Prospects, With Special Reference To The Spread of the Gospel”, was first published in May 1838. This 852-page tome had a powerful impact upon many, including J. Hudson Taylor, who “immersed himself in it” and came away convinced that medical missions were the best way to reach the Chinese. When Taylor, nearly penniless and without any friends, landed In Shanghai, he was “cast upon the hospitality of Medhurst. He found Medhurst was more experienced and knowledgeable about China than any other Protestant missionary.” Medhurst advised Taylor to start by learning Mandarin, the language of officials that was spoken throughout much of China. Medhurst gave him his textbook for learning Chinese and sold him his Chinese dictionary for half the usual price. He also invited Taylor to dine with him many times, and regularly had him for tea before each weekly community prayer meeting. Significantly, in 1855 he advised Taylor to adopt Chinese dress, as Medhurst himself had done temporarily in 1845, leaving detailed instructions on the process in his book “Glance at the Interior of China”.

Though he may not of led many souls to Christ himself, Medhurst deeply impacted one man who did through the China Inland Mission - James Hudson Taylor. Medhurst died on January 24, 1857, in England. The first generation (Medhurst) had ushered in the second (Taylor).

Source Wikipedia and Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Christianity (BDCC)